I have been thinking for some time that I am finally ready to tackle LFS, and since my nix config files have reached a point where I feel ok letting them sit (the self sufficiency guide is also going along nicely), and since I have a small workstation computer that runs said nix configuration, I decided that now is the time to make my truly own linux distro.

The plan is simple: I follow LFS to set up a bootable TTY, and from there I will start writing my own nix/guix like package manager and configuration system in Nim. Wait, Nim? What’s Nim?

Nim is a statically typed, compiled language, which shines at metaprogramming. Specifically, its macro system allows a piece of code to update the AST at compile time, unwrapping said macro into nim code. Needless to say, this is extremely powerful, since it allows anyone to create domain specific languages (DSLs), or to do laborious calculations at compile time (my first experience with nim’s macros was the implementation of macros to declare neural networks in the arraymancer library, by mratsim. You define the network layers and the forward function, and the compiler unwraps the network at compile time into how pytorch sort of looks like; another usecase I might look into at a later time is compile time FFT or Laplace transformations for QM. Another idea could be for cryptography (maybe lattice based? Who knows? Certainly not me.)).

Assuming a successful LFS installation, using sysvinit (I plan on making my own init system later down the line), nim comes into play immediately after LFS+wget.

LFS was simple enough to get running1. The book is extremely well written, so it is just a matter of correctly following the order of operations. Then, for wget, its a matter of being the package manager, ie following the dependency tree down to the roots, and building up. Both of these processes also build intuition for how the package manager ought to behave.

In any case, wget is important because it is both how we will access the source files to build each package, but also allows us to install grabnim. grabnim is a standalone binary for managing different versions of the nim compiler; the nim compiler itself is also a standalone binary, and it uses gcc to compile .nim files into binary; we already have gcc because it was installed during the build of LFS. This means that having access to wget (or curl, but curl is more tedious (more dependencies)) gives us access to the entire nim ecosystem.

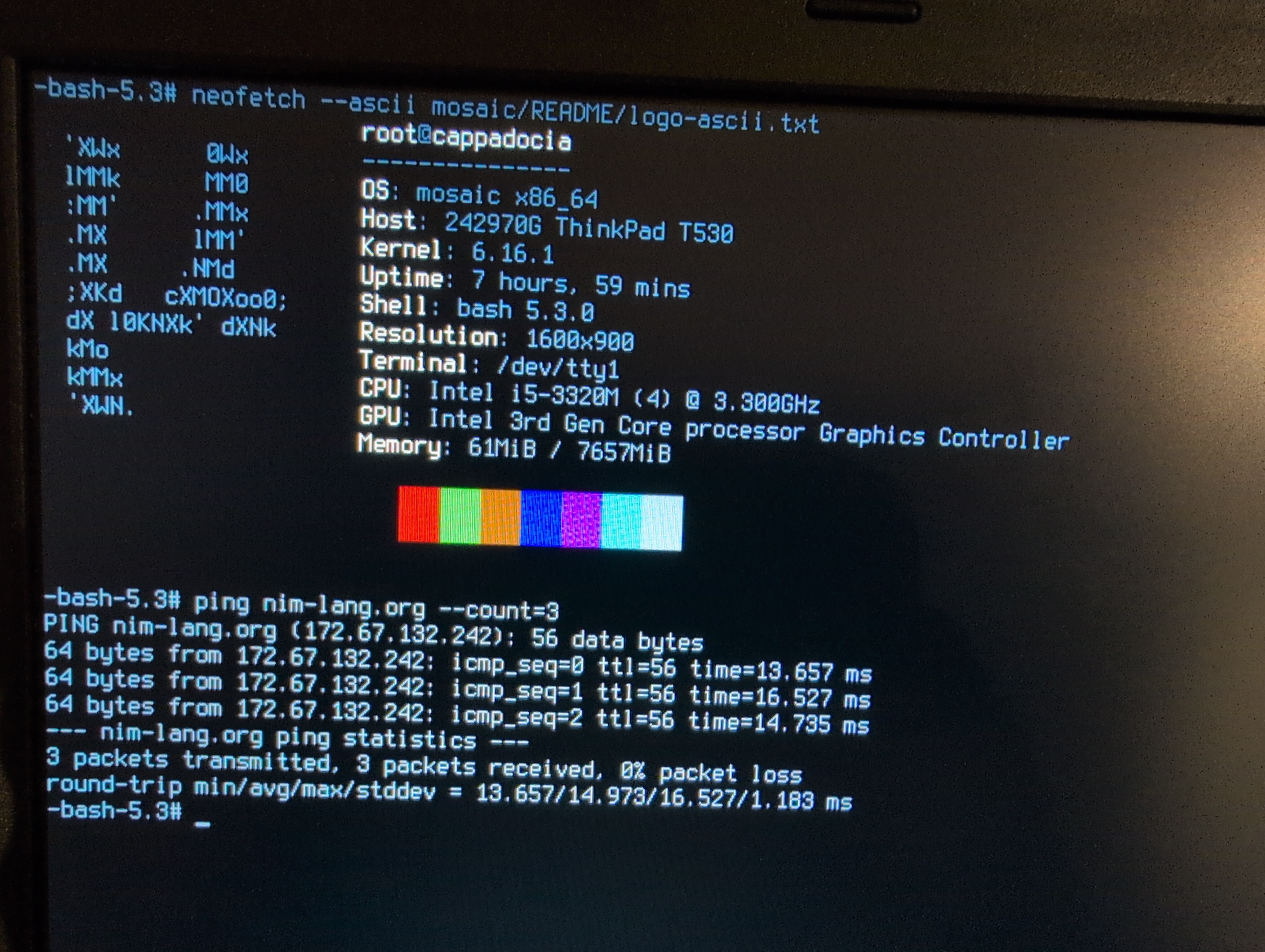

Very importantly, and before we get into the weeds, let us change the distribution name from Linux From Scratch to mosaic, and the codename to ravenna. Let us also import a draft ascii logo and call neofetch (neofetch is a bash script, so its super easy to install)

Now that LFS is installed, the first thing that a package manager should do is maintain itself, as well as the system. This will also allow me to build the skeleton of what the package manager will be. In my case, this means that I first started with building git, which would allow me to sync and keep track of my progress. This also “forced me” to come up immediately with the package definition scheme.

Nim’s power for this specific usecase is, as mentioned before, its powerful metaprogramming via macros (soon to be compiler plugins in nim 3), meaning that we can replicate and even simplify the package definitions for Arch Linux (PKGBUILD), or Alpine (APKBUILD). Let’s see how a package is defined.

Keeping up with the mosaic theme, a package definition is called a tessera, from Greek τέσσερα meaning four (in the case of tessera, four sides2).

A tessera incidentally needs five definitions:

- the source of the package (uri)

- any extra patches that need be applied

- the list of dependencies

- the build script

- one of the output files to verify installation

with each one of those taken from the LFS/BLFS book depending on each tessera.

Each one of those, bar the fifth one, should be obvious as to why it is needed, and the fifth is an unfortunate necessity, at least until I move on to building mosaic properly, including a lockfile. I personally feel it takes from the elegance, but at the same time the system is “good enough” especially for a pre-alpha. In any case, let’s see how git is defined, since that’s our ultimate goal, at least initially.

The tessera git is defined as

import .. / lapis # the macro implementation

# definition of git

tessera "git":

source: "https://www.kernel.org/pub/software/scm/git/git-250.1.tar.xz"

patches: @[""]

dependencies: @[

"curl",

"fcron",

"pcre2",

"valgrind",

"gnupg",

"iosocket_ssl",

"openssh",

"subversion"

]

build: @[

"""

./configure --prefix=/usr \

--with-gitconfig=/etc/gitconfig \

--with-python=python3

""",

"make",

"make man",

"make perllibdir=/usr/lib/perl5/5.42/site_perl install",

"make install-man"

]

result: "git"Simple huh? We have declaratively defined everything needed to build git. But Nimlang isn’t a functional programming language so how does this work? In essence the macros of nimlang are so powerful that I am able to define a functional domain specific language (DSL) that takes exactly these 5 keywords:

source: string,patches: seq[string],dependencies: seq[string,build: seq[string]result: string

and which, at compile time, unwraps into an iterative process. For anyone interested, lapis, the DSL definition is found here3. Suffice to say, it is my first take at a macro, and this is, once again, pre-alpha, so it will hopefully get better with time.

Now that git is here, all we need to do is to follow the dependencies tree, in order to define evey package that git needs4, as per the BLFS book, and create a tessera for each.

-

The LFS installation process could also be automated via a nim binary/installer, should others wish to try the distro. ↩︎

-

A cube has more than four sides, however in a mosaic each tessera is perceived as a square. ↩︎

-

To be released. ↩︎

-

I purposefully didnt include every optional dependency in the BLFS book when packaging git. The aim is to do a DIY distro where it easy for every person to manage their own packages. ↩︎